“Sugar” Ray Seales has truly lived a surreal life, to say the least, and he’s still involved in boxing at the age of 67 as a successful coach of amateur boxers in Indianapolis.

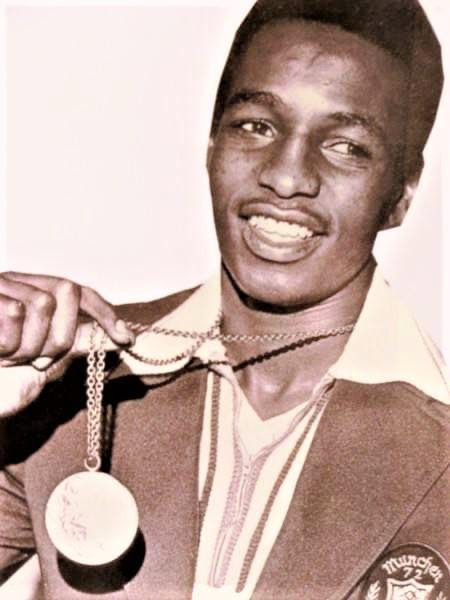

Imagine being the lone boxer from your country to capture an Olympic gold medal only days after the infamous Munich massacre.

Now imagine also having won a remarkable 338 of 350 amateur matches, having fought a trilogy as a professional with “Marvelous” Marvin Hagler, being declared legally blind in both eyes [having entertainer Sammy Davis, Jr. pick up a six-figure medical bill], regaining sight in one eye, then working as a teacher of autistic students for 17 years.

Born in Saint Croix, U.S. Virgin Island as one of eight children in a family whose father was a boxer there as a member of the U.S. Army team, Seales started boxing at the age of nine. “I have three brothers and we always beat the crap out of each other,” he spoke about his start in boxing. “Learning how to box, for me, was all about fighting to be the first to eat. I had gotten hit in my left eye playing dodgeball and my uncle, who was stationed at Ft. Lewis (in Tacoma, WA), told my mother there was a special doctor there who could help with my eye. My father was stationed all over and in 1964, when I was 12, my mother moved us to Tacoma, Washington.

“I had boxing in my system. So I went with my brothers to the Downtown Tacoma Boys Club, which was only one block from our home, and my mother could watch me walk from our house to the gym and back. I was the first from there to win a Golden Gloves title. But I wanted to be a winner and finished with 14 (champion) jackets. I couldn’t speak English. I knew Spanish and spoke Spanish and English together. The first word I said in English was box. We used to fight three or four times a day and we built the Tacoma Boxing Club. I went on to have a 338-12 amateur record and I’ve been in boxing ever since.”

Seales developed into a champion, taking top honors at the 1971 National AAU and 1972 National Golden Gloves championships. At the age of 19, Seales enlisted in the U.S. Air Force, but his mother made some calls so Ray would be able to compete in the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich, Germany.

She succeeded and the rest, as they say, is history. And when he came home from the Olympics, he was told that there was no need for him to report to the U.S. Air Force, because he had done enough in terms of service as the only American boxer to win a gold medal.

The 1972 Olympics, however, was overshadowed by the killing of 11 Israeli athletes and coaches, as well as a West German police officer at the Olympic Village by terrorists on Black September.

“I had just turned 20,” Seales remembered. “Boxing was heavy when we went there. Some of my family, my coach from Tacoma, and Tacoma teammate (and 2-time U.S. Olympian) Davey Armstrong were in Germany. I didn’t know anything at first. But I had to get the attention of my parents to let them know not to go there, because there were terrorists with sub-machine guns in the Olympic Village. I was the only American boxer left to fight.”

Seales defeated Bulgarian Angjei Anghhelov, 5-0, in the light welterweight championship to capture an Olympic gold medal, the only member of the U.S. team to do so. His teammates included Armstrong, Duane Bobick, and Olympic bronze medalists Jesse Valdez, Marvin Johnson and Ricardo Carreras.

Sugar Ray Seales’s dedication to USA Boxing is second to none,” said Chris Cugliari, USA Boxing Alumni Director. “His pride, patriotism, and devotion to helping our next generation of champions is what makes him such an inspiring figure.”

Seales turned pro in 1973, winning an 8-round unanimous decision over Gonzalo Rodriguez in Tacoma. “Sugarman” won his first 21 pro fights, until he lost a 10-round decision to 14-0 middleweight prospect and future Hall of Famer Marvin Hagler. Two fights later, Seales fought Hagler in Tacoma to a 10-round draw (99-99, 99-99, 98-96).

“Everybody wanted a shot at the Olympic gold medalist,” Seales explained.” I went to Boston and we fought in a TV studio (WNAC). It was freezing in there. I was shivering when I went into the ring, Marvin came out dripping sweat. But I knew I was losing after seeing that, but I hung with him and went the distance (10 rounds). I was having management problems and three months later I fought Hagler again, only this time at home in Tacoma. I beat him but it ended in a 10-round draw. He knows I beat him!”

Ray Seales vs Marvin Hagler

Seales completed his trilogy with Hagler. But it was five years later, when Hagler was 42-2-1 and avoided by most of the world’s top middleweights.

“I was the USBA (United States Boxing Association) and North American Boxing Federation (NABF) middleweight champion. Hagler needed to win a title to get a world title shot,” Seales noted. “I lost our third fight in the first round. But that’s the only thing shown on television in our three fights.

“We were two left-handers, but he switched to right-handed/ He caught me with a hook. I got paid, and they bought him a world title fight.”

Seales has coached two different amateur teams in Indianapolis during the past 11 years, winning 10 Golden Gloves team championships, and he’s still in charge in Indy of Team IBG.

After he retired in 1984 after suffering detached retinas in both eyes, Seales was introduced in Las Vegas to Sammy Davis, Jr. (pictured below), who paid Seales’ $100,000 medical bill for his damaged eyes. Davis had lost his left eye in a 1952 car accident

“I’m a teacher,” Seales concluded. “I see the way that so many boxers want to fight like Floyd Mayweather. Their head is tilted, they can’t throw a jab.

“I teach them to have the right foot behind the left (for a right-handed boxer), and to walk in straight, not tilted or peaking. Heel toe, heel toe every time you pivot is your stance.

“My advice for the boxers who hope to compete in the 2020 Olympics is to focus on what you’re doing and listen to how to get it done. What I really want to do is to coach the USA Olympic Boxing Team 2024.”